A Dumb Brain

tl;dr — how a kraken learns to classify and saves the world

October 22, 2014

Brains are awesome. I think we can agree on that. Without a brain, we would be only some cells floating around in the mighty oceans – a jelly- or starfish at most. You couldn’t read this. I couldn’t write it. We couldn’t think, feel, do math, code, sing, compose, or even bake some banana bread. Some would even claim the brain is the most complex structure in the Universe. I wouldn’t disagree. More precisely, my brain wouldn’t disagree.

Also, some brains can be megalomaniac.

The human brain has reached such a complexity that we even try to understand our own brains. Brains pondering over brains. That’s so meta and poetic at the same time. We’ve even been trying to emulate brains with fast but dumb computers more or less since the 1960s – with little success, though. There was even a serious depression going on called the AI winter. I am not making this up. Actually, there were two winters.

Back then, Artificial Intelligence was supposed to be the next big thing. Everyone was talking about it, but then some people realized very little progress had been made toward this quite challenging endeavor. Funding was cut. Research was stopped. Since then the most successful “intelligent” algorithms have been statistical methods. We are talking about a lot of number crunching here. Very fast. Something a computer is very skilled in, but not something we would describe as “intelligent” at all (whatever that might mean).

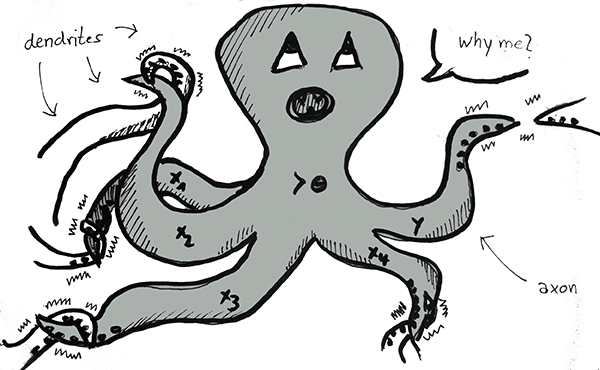

Perceptron

Central to all brainy ambitions are neural nets – the most direct approach to mimic the brain – with its most basic building block the Perceptron. It is as basic as its role model, the neuron. I am not going to try to explain a neuron at all (I don’t want to be killed by a raging biologist), but I will give you an image you can work with. Picture a kraken with two types of tentacles. Most of its tentacles are dendrites, and the biggest and longest of them is the axon. The dendrites continuously receive electrical pulses from surrounding krakens, and, if together the pulses exceed a certain threshold, the axon will fire a pulse to another kraken. That’s how our brains work. I swear. There are 100 billion krakens in your head. Why does this work? How do all these krakens enable us to do things like make banana bread? Nobody really knows. That’s the mystery of our brains and why we still do not have robots which try to kill us.

</img>

</img>A Perceptron is exactly like a kraken, just with a touch of math. It gets some input to its dendrite-tentacles, adds them up and outputs +1 if they exceed a threshold and -1 otherwise. That’s it. Although a single Perceptron seems to be pretty dumb, it is remarkable what you can achieve with this simple concept.

Let’s put this into a formula.

Our kraken gets numbers as input , multiplies each of them by some weird , and tests if the sum is greater than the threshold . The s are actually weights and they are like the diameter of the tentacle which determines how much electricity will be carried. The smaller the weight, the less impact this particular tentacle has on the sum, and with a negative tentacle diameter – I don’t want to even think about that.

If you have studied some math, you have maybe spotted something very similiar. Have you ever seen anything like this?

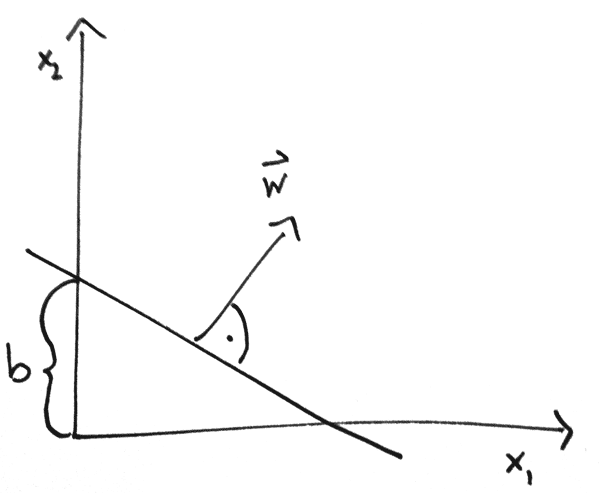

</img>

</img>This is a special form to represent a hyperplane in space. Since not everybody can think in multiple dimensions like Stephen Hawking, we are going to choose the special case of , which is representing a line on a two-dimensional plane. There is also an easy way to visualize this formula. The vector is perpendicular to our line, so by pointing somewhere in space we determine the slope and by adding a bias we manipulate the intersection between the line and the axes. Every point that satisfies this equation is exactly on our line. The other interesting property is that every point which yields a positive value instead of zero is above the line and every point which yields a negative value is below the line.

If you look closely, you might see that our Perceptron isn’t so much different. Rearranging the formula, think of as , replace with and you will see that our Perceptron is nothing else than a line in space.

By the way, if feel too unfamiliar with this representation, you can easily rearrange it to the more common “slope-intercept” form . Feel free to do this in your spare time. I will give you a hint how it will look in the end, though.

So, basically, our two-armed kraken is a linear classifier by exploiting the “interesting property” of this hyperplane representation. The weights and the threshold determine which function it represents to separate the space into two classes.

</img>

</img>Now the more important question: So what?

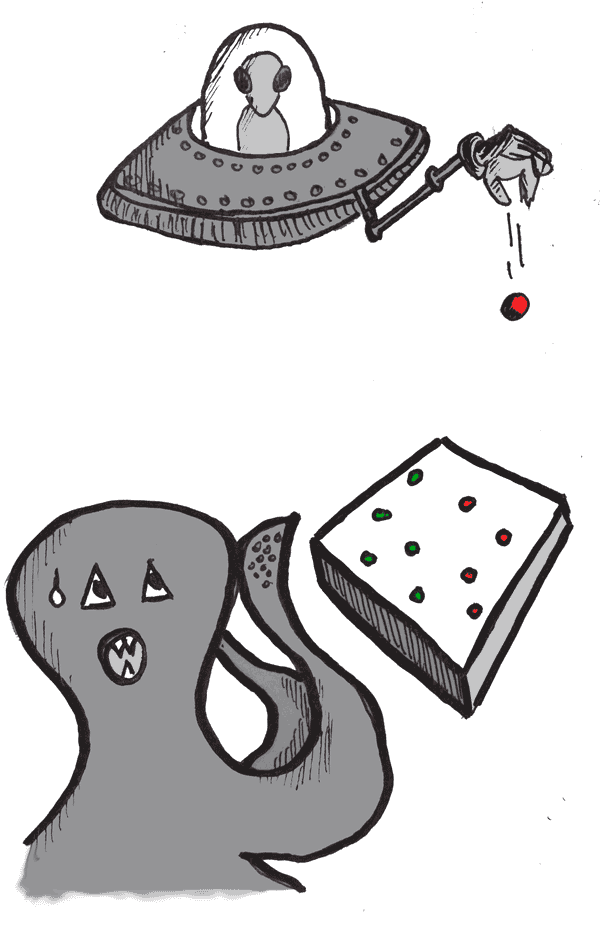

Let me come up with another ridiculous, but tremendously helpful and life-saving analogy. You are playing an ancient game that is actually older than both Chess and Go together. It is so old that nobody can remember its name anymore. The board is a two-dimensional field and there exists a line which splits the board in two. You do not know anything about this line except that it is a straight line. From time to time you get some hints. They fall as tokens from the sky on your board and in addition to its position they have one of two colors which indicates where the token has landed – red if it is below the line and green if it is above. Your goal is to approximate the line as good as you can, so if a grey tokens falls down you are able to paint it either red or green. That’s it. Have I mentioned that the world explodes with a big bang if you paint it in the wrong color? That is maybe one of the reasons nobody plays it anymore. You are forced to play it anyway – by some masochistic alien from the delta quadrant.

But no worries. Your time has come to use your secret weapon.

Release the kraken.

Training

In the beginning we do not know anything at all. The only thing we can do is take a guess. We randomly assign some values to the weights and the threshold. After we get some clues we can correct these weights to give a more educated guess in the future. In machine learning this is called supervised learning. You feed your algorithm a training set to build a model, which is going to be applied on unseen data to predict its class (or real numbers in case of a regression task – but, ehmmm, nevermind).

How you adjust your weights is up to you. You are the kraken tamer. You could use a fancy genetic algorithm or any other optimization method, but that feels like taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut. It is actually way easier. For every with its expected output and the current guess of the prediction, we change like this:

Basically we add the current training point to the weights. This causes the vector to point slightly more in the direction of the misclassified point. At least for the case where you have to move the line “up”. In the case where you have to move the line down, you have to subtract the vectors. This is actually done by the error term, which is either positive or negative for each respective case. Additionally, if the error is zero – i.e. our kraken was absolutely right with its decision – we do not change anything. Neat. Everything we want. But what is this strange doing over there.

Usually this is a relatively small constant – like or . The concept behind this is called “smoothness” and is quite common in a lot of learning and optimization algorithms. Without this constant our kraken would be jumpy and would overshoot fairly often. In general you are going to be more precise if you do a lot of small steps instead a few big ones, which brings us to the next part.

You will not apply this learning rule only once for every point. In fact several iterations over the whole training set are necessary to train a master of a kraken. Repetition is the core concept of learning – whether kraken or humanoid. In case you forgot: We are talking about brains!

I might hear you asking: When shall we stop? Will it run forever? Excellent questions. If (and only if) the “real” function we have to learn is linear, some crazy math can prove that these weight adjustments will converge – i.e. stop after a finite number of iterations with 0 errors on the training set. Of course we can never prove that we will never make an error on unseen data since we have never seen the “real” function. Now you can see why these aliens are notoriously masochistic. However, according to the seen training data, we have done the best we could do to save the world.

If you ever come up against the nonlinear sequel of this game, don’t miss part II of this post: “How a mob of krakens defeated a nonlinear attack from outer space.” Coming soon.

And if you are not completely convinced by this approach, I set up a simulation of this game where you can safely play around without the world being at stake. Add random data to the canvas, press learn, and move the slider to explore the kraken’s state after each iteration. And do not forget: orange points mean death to all of us!